Jason Francisco / View of the Venetian Harbor, Chania

Jason Francisco / St. Nicholas Church, formerly the main mosque of Chania

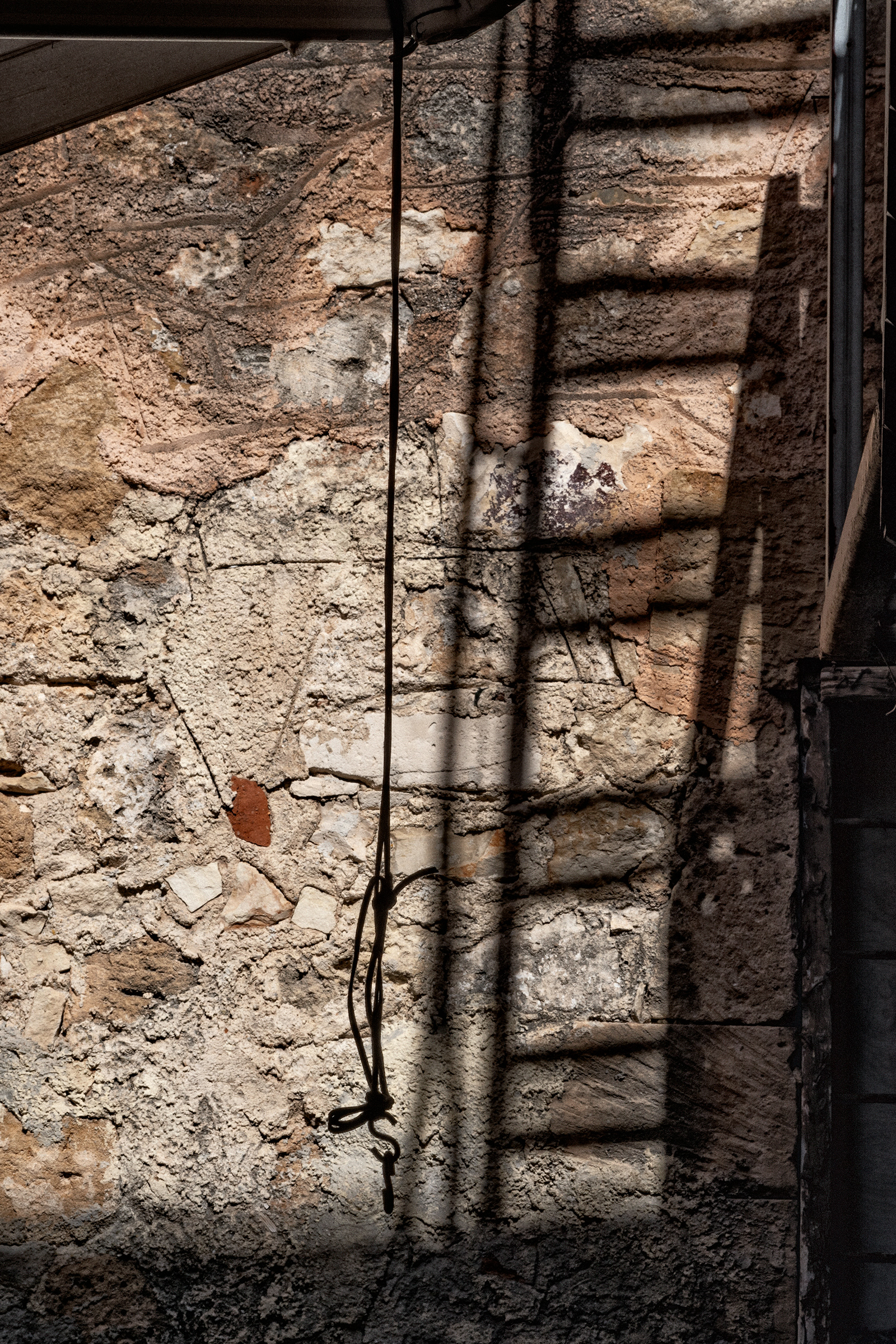

Jason Francisco / Fundaments of the Venetian city, Chania

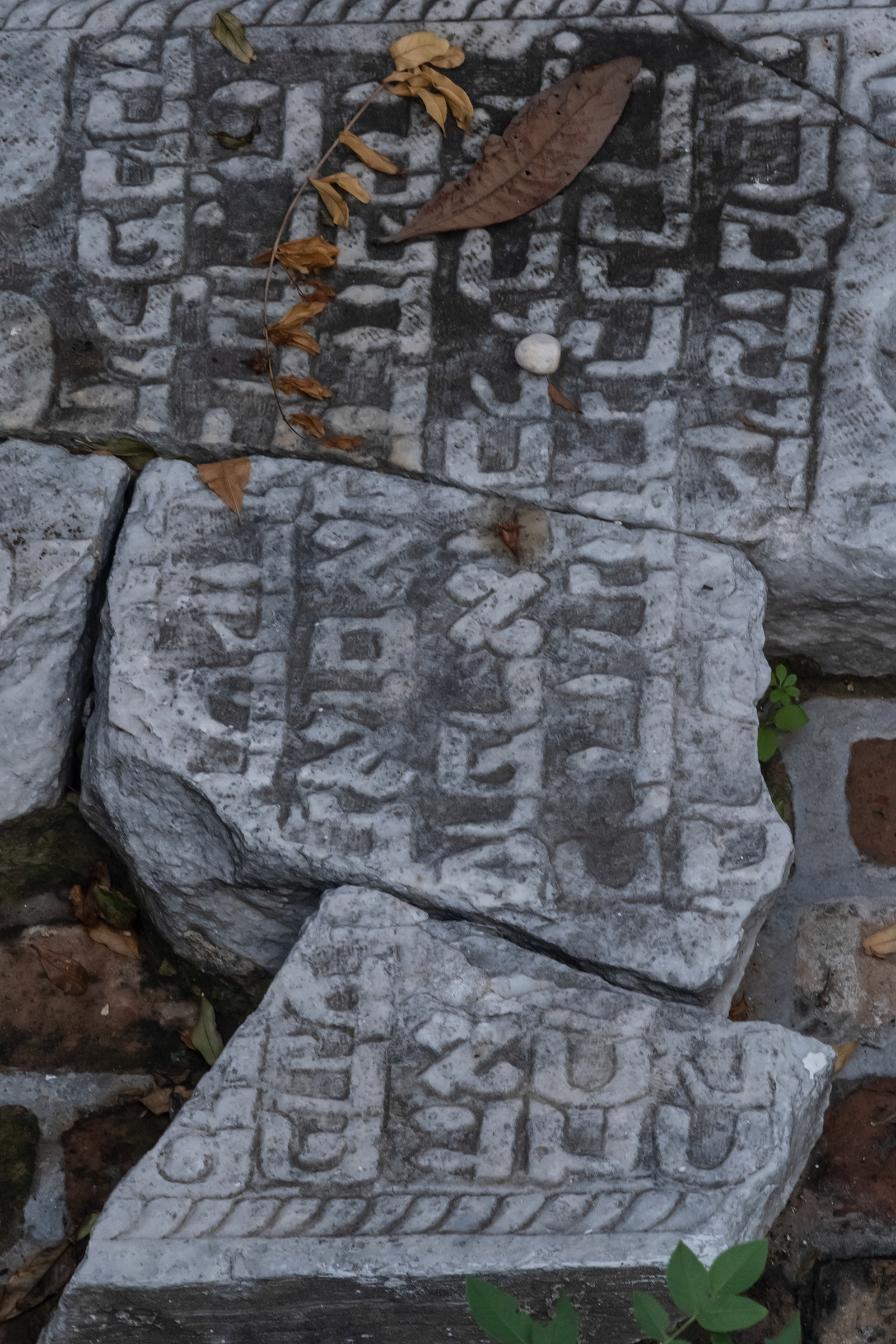

Jason Francisco / Excavation of the ancient Minoan city beneath Chania

Jason Francisco / The old city, Chania

Jason Francisco / The seawall, Chania

Jason Francisco / The Venetian Harbor, Chania, looking north on a calm day in winter

Jason Francisco / Panorama of Chania looking south from the lighthouse in the Venetian Harbor

Jason Francisco / Panorama of Evraiki looking north. The photographs below explore the streets of Evraiki, Chania's old Jewish quarter.

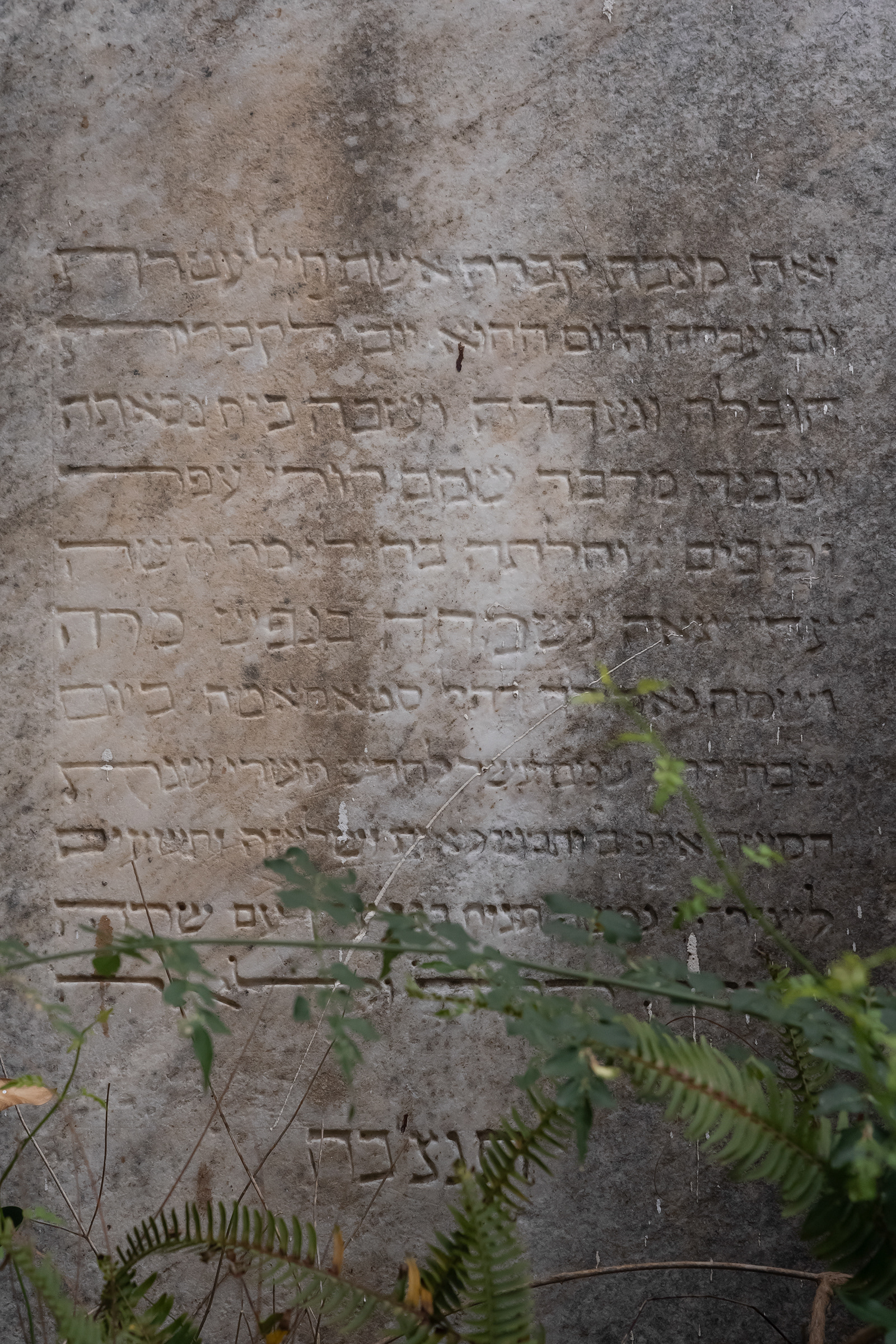

Jason Francisco / View from the window of the erstwhile home of Chania's rabbis on Kondylaki street. Before the Holocaust, Chania's largest synagogue, Beth Sholom, stood precisely where building with the grey roof now stands, blocking the view of what is today the terra-cotta colored building with the green windows.

Jason Francisco / View of Etz Hayyim synagogue, 2023

Probably Nikos Stavroulakis / Etz Hayyim before renovation, c. 1995. Below: Jason Francisco / Etz Hayyim's spaces, 2022-2023.

Jason Francisco / View toward the bimah in the Etz Hayyim sanctuary

Photographer unknown / Nikos Stavroulaikis, n.d.

Photographer unknown / Nikos Stavroulakis, Chania, n.d.

Jason Francisco / Athens, Statue of Metropolitan Damaskinos in front of the city's main cathedral. Damaskinos was the only head of a European church who openly called for the end of Nazi persecution of Jews.

Jason Francisco / Left: The Acropolis and the Ancient Agora, Athens; Right: Tile from an ancient synagogue once located in the Agora, on display at the Jewish Museum, Athens.

Jason Francisco / Left: The bimah of a synagogue in Patras saved during the building's demolition, now in the Jewish Museum, Athens (this bimah served as the model for the reconstructed bimah at Etz Hayyim); Right: The destroyed and overbuild Jewish cemetery of Patras, the bones still in the ground.

Jason Francisco / Left: The destroyed and overbuilt Jewish cemetery in Arta, bones stil in the ground; Right: Memorial to the Jews of Arta

Jason Francisco / Left: Renovated but community-less synagogue, Veria; Right: The destroyed and overbuilt Jewish cemetery of Veria, bones still in the ground.

Jason Francisco / Left: The intact "new" Jewish cemetery of Ioannina; Right: The destroyed and overbuilt old Jewish cemetery of Kavala, bones still in the ground.

Jason Francisco / Left: Inside the Romaniote synagogue, Ioannina; Right: Street in one of three former Jewish districts of Ioannina.

Jason Francisco / The warehouse in which the Jews of Xanthi were imprisoned before their deportation and murder in the Holocaust (site unmarked).

Jason Francisco / Left: The site of the destroyed synagogue of Xanthi (next to which is a day care center, hence the capriciously dark mural of a train); Right: New memorial to the Jews of Xanthi, dedicated 2023.

Jason Francisco / Left: The synagogue of Larissa; Right: Memorial to the murdered Jews of Larissa.

Jason Francisco / Left: The main cathedral of Thessaloniki, whose construction utilized headstones from the Jewish cemetery, some of which remain in the side yard; Right: The ancient Jewish cemetery of Thessaloniki, now Aristotle University, bones still in the ground.

Jason Francisco / Left: Deportation platform from which the Jews of Thessaliniki were deported during the Holocaust; Right: Display in the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki.

Jason Francisco / Serres, the destroyed and unmarked Jewish cemetery

Anja Zuckmantel, Director of Etz Hayyim, leading a tour of Evraiki, the historic Jewish quarter of Chania.

Jason Francisco / Rosh Hashanah, Etz Hayyim 2022

Jason Francisco / Taschlich at the Venetian Harbor, 2022

Jason Francisco / Rabbi Dr. Nicholas Delange, rabbi of Etz Hayyim

Jason Francisco / Sukkot at Etz Hayyim 2022

Jason Francisco / A visitor shaking the lulav in the sukkah of Etz Hayyim, 2022

Jason Francisco / Volunteers at Etz Hayyim taking a break from their studies

Jason Francisco / Iosif Ventura, renowned Greek Jewish poet, Holocaust survivor originally from Chania, at Etz Hayyim's International Holocaust Remembrance Day events, 2023

Jason Francisco / Nick Germanacos, poet, 2023

Jason Francisco / Ruth Padel, poet and novelist, 2022

Jason Francisco / Beznik, the shammes of Etz Hayyim

Jason Francisco / A portrait of Thora, Etz Hayyim volunteer

Jason Francisco / Pesach at Etz Hayyim, the community seder, 2023

Jason Francisco / Shavuot at Etz Hayyim, study session with Rabbi De Lange and Father John Raffan, 2023. At the far left is the Metropolitan of Chania.

Jason Francisco / The dedication of a new Torah scroll in honor of Nikos Stavroulakis, Shavuot, 2023

Jason Francisco / Carrying the new Torah, Shavuot, 2023

Jason Francisco / Annual memorial service for the victims of the Tanais, with Rabbis De Lange and Gabriel Negrin, 2023

Jason Francisco / Anja Zuckmantel welcoming a group of visitors

Jason Francisco / Father John Raffan, longtime friend of Etz Hayyim and a personal friend of Nikos Stavroulakis, carrying the new Torah scroll dedicated in Stavroulakis' honor, Shavuot, 2023. This moment was, for me, an emblem of so much that is unusual at Etz Hayyim. and the community's soulfulness.