“It was inconclusive. It was always going to be inconclusive. What do we do with the unknowable? What can we do but embrace it? Let our stories leak, become diffuse and imprecise.” —Menachem Kaiser

“The fist is coming out of the egg” —W.S. Merwin

Osówka

1. “Riese” (“Giant”) was the code name for a major infrastructure project of the German government in 1943-1945 in the Owl Mountains of Lower Silesia, formerly in Germany and today in Poland. The precise purposes of the project remain uncertain—researchers speculate that it was to have been an elaborate underground city, perhaps a bunker and command center something like the Cheyenne Mountain Complex of the U.S. government in Colorado.

Construction on Riese began in the fall of 1943, initially using forced labor of Soviet and Italian prisoners of war, and Poles captured in the aftermath of the 1943 Warsaw Uprising. A network of roads, bridges, and narrow gauge railways connected the town of Wałbrzych with several cavern complexes whose German code names are unknown, called today by Polish names created after the war. These include the Książ Castle complex, the Rzeczka complex, the Włodarz complex, the Osówka complex, the Sokolec comples, the Jugowic complex, the Soboń complex, and the Jedlinka Palace.

In the spring of 1944, dissatisfied with the progress of the work, Hitler reorganized and intensified construction efforts. Slave laborers of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp were assigned to Riese, operating from thirteen subcamps in the vicinity of the town of Głuszyce. We know that some 13,000 prisoners, mostly Jews, worked on Riese until May 1945. Three quarters of them came from Hungary, and the rest from Poland, Greece, Romania, Czechoslovakia, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany. Mortality was high, owing to the dangerous working conditions, the brutal treatment of guards, malnutrition, and disease. We know that many prisoners cycled through Gross-Rosen and the Riese sites to and from Auschwitz and other camps, and we know of 14 executions of Riese prisoners after failed escape attempts. The exact numbers of victims will never be known, but certainly in the thousands.

Another typhus epidemic slowed work toward the end of 1944, and the approaching Soviet army led to evacuations west into Germany, though work on the Riese complex continued into April 1945. The Soviet Army arrived in May 1945 to find a few prisoners and the uncompleted tunnel systems, shelters, and earthworks. Today, these relics remain sources of fascination for local explorers, and three of the sites—Książ, Włodarz, and Osówka—have been transformed into public attractions.

Kaltwasser

Kaltwasser

Kaltwasser

Kaltwasser

Kaltwasser

2. A key source of information about Riese is the Holocaust memoir of Abraham Kajzer, titled Za Drutami Śmerci (“Behind the Wires of Death”). A Jew from Będzin, Poland, Kajzer was thirty years old when he arrived at Gross-Rosen in the summer of 1944 in a transport from Auschwitz, where his wife and son were murdered. Kajzer worked in at least eight Riese subcamps. He chronicled his experiences in a diary written in camp latrines on scraps of cement bags, which he nailed to the insides of the boards where prisoners would shit. Had his writings been discovered, it certainly would have meant his death. Following his escape in April 1945, Kajzer was hidden by a local German woman, and survived by living in a wooden box filled with potatoes. We now know that Kajzer’s savior was also his lover, as Menachem Kaiser details in his 2021 memoir Plunder: A Memoir of Family Property and Nazi Treasure (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021). At the war’s end, she gave Kajzer a bicycle, with which he returned to the latrines of the camps and collected his pages.

How Kajzer’s manuscript saw publication is a remarkable story. In 1947, he brought the cement bag writings to Adam Ostoja, secretary of the Łódź Association of Polish Writers. “He wanted me to develop it into a literary work,” Ostoja writes in the preface to Za Drutami Śmerci. Presumably with Kajzer’s assistance, Ostoja created a narrative not in the Yiddish in which Kajzer wrote, but in Polish—making the text at once a translation and an original. In Kaiser’s fascinating exegesis, it is “not quite a diary and not quite a memoir but something like a diary wrapped inside a memoir…a kind of Nabokovian realization.” The manuscript was finished in 1948, but for unknown reasons not published. When Kaiser emigrated to Israel, he brought with him a copy of the Polish manuscript and had it translated into Hebrew, where it was published as Bein Hamitzarim (“Dire Straits”) in 1952. The Polish text was finally published in 1962, with the Hebrew edition unknown to Ostoja. In Kaiser’s words, “Za Drutami Śmerci and Bein Hamitzarim tell the same story, in more or less the same style, using more or less the same language… [y]et they are different books: they exist on different planes. They entered distinct worlds with no tether between them… Bein Hamitzarim is a noble but insignificant book; Za Drutami Śmerci is a significant but ignoble book.”

In 2024, the University of Toronto Press will publish an English edition, with annotations and a concordance between the Polish and Hebrew versions, plus commentaries by Menachem Kaiser and the Gross-Rosen historian Dorota Sula.

Tannhausen

Tannhausen

Tannhausen

Tannhausen

Tannhausen

3. Menachem Kaiser is, yes, related to Abraham Kajzer—Kajzer was the first cousin and closest surviving relative of Kaiser’s paternal grandfather—and it is through Kaiser that my own work on, or more accurately, from Abraham Kajzer came to be. Kaiser and I first traveled together through Lower Silesia in the summer of 2016, along with our friend Maia Ipp. Kaiser was working on Plunder and I on Alive and Destroyed: A Meditation on the Holocaust in Time (Daylight, 2021), for which Kaiser wrote the Afterword. We spent days in and around the Owl Mountains, in Książ and Osówka and Soboń—the latter entered through a small nondescript hole in the mountainside, into which we slogged in knee deep water in pitch darkness. We were passed from hand to hand in the strange and fascinating world of Polish treasure hunters, adventurers, seekers after golden trains, amateur historians, conspiracy theorists, occultists, fabulators of Nazi “science”—some claiming expertise in Nazi time travel—and one memorable “Count” in camouflage fatigues, swearing that the rancid water in his cistern had rare healing powers. Through our journeys, I photographed continuously with my Leica, as is my wont.

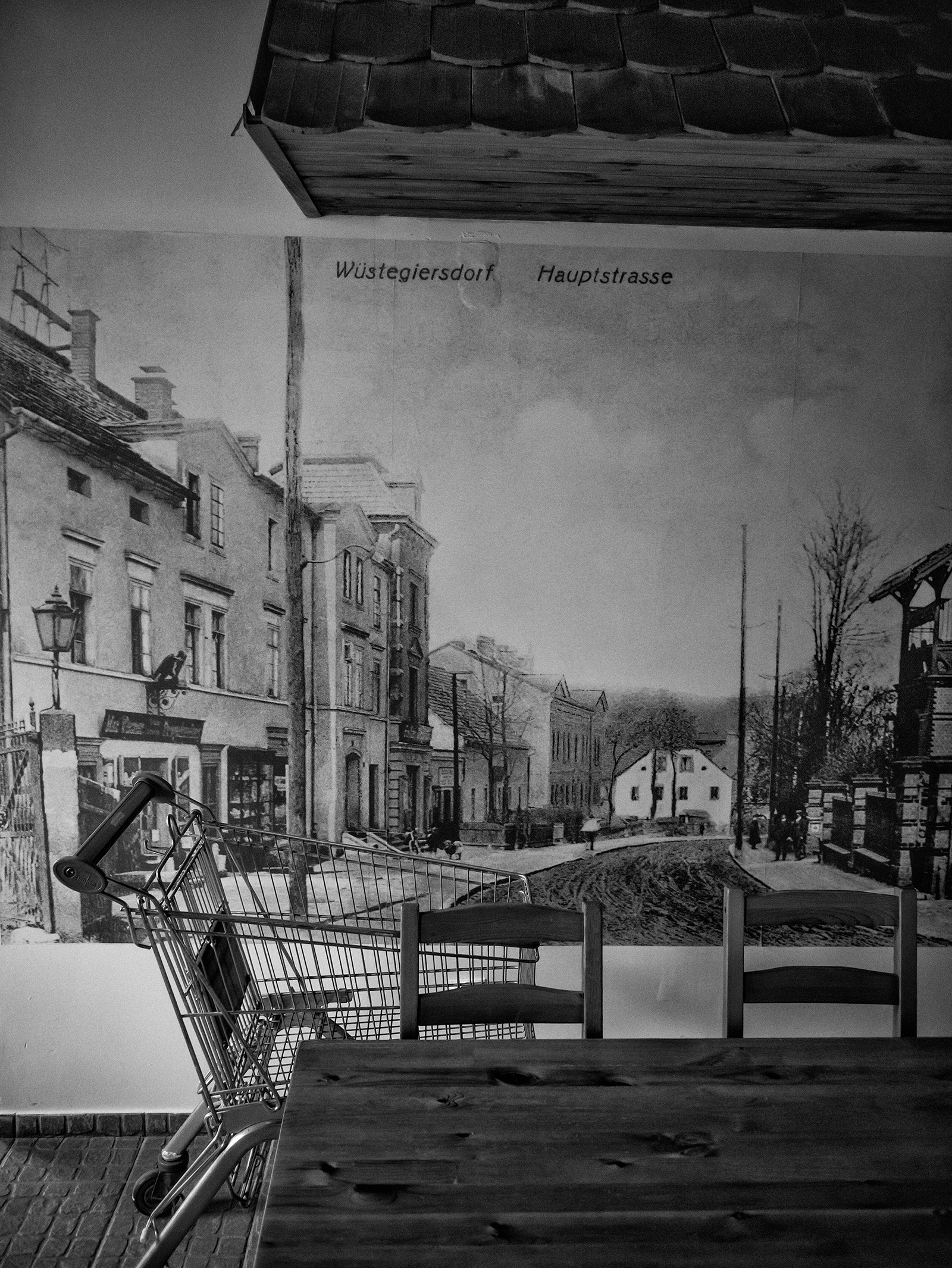

In April 2023, Kaiser and I were again in Lower Silesia, this time with our friends Scotia Gilroy and Michael Rubenfeld. Over several days, we made our way to the locations of all eight of the Riese subcamps Kajzer describes in his book—Kaltwasser, Tannhausen, Wüstegiersdorf, Lärche, Wolfsberg, Schotterwerk, Dörnhau, Erlensbuch—plus Osówka, Włordarz, and Gross-Rosen. Some of the photographs I made in these sites will be included in the University of Toronto Press edition. Many more than will appear there are here, on this webpage.

Wüstegiersdorf

Wüstegiersdorf

Wüstegiersdorf

Wüstegiersdorf

Wüstegiersdorf

4. It is not obvious why to include photographs in the English version of Kajzer’s text. Because they are contemporary photographs, they are not visual annotations in a straightforward sense—certainly not what period photographs of the same sites would be, for example, if they existed. Maybe they will contribute what could be called “information” in some very simple sense. Presumably the light in Lower Silesia in April 2023 resembles the light in Lower Silesia in April 1944, and maybe Kajzer would recognize something about the flora and the lay of the terrain or certain structures, were he alive today to see my photographs. But informational transference of even this kind already requires significant acts of imagination, so much so that ‘information” seems to me all but indistinguishable from artistic conceit.

There is a lot I could say about photography’s inner workings—its inner unrest, inner irresolutions—as reasons to include photographs as visual complements to Kajzer’s testimony. I could name, for example, other modalities in which I think photographs operate, apart from the visualization of information. Just as photographs have the power to bring what is present as vision to (new) presence as image, they have the power to remove present things from presence. Just as photographs have the power to make us envision what is (evidently) visible, they have the power to dissipate our awareness of the whole in favor of the part we are given to see. Just as photographs (outwardly) reproduce what they show, they change what they reproduce, sometimes subtly and sometimes drastically, but enough—as photographers know—to call into question any simple idea of what things “really” look like, or are, apart from the ways we feel them and think them and, subsequently, see them.

More than three decades now into a life in photography, I can distill the way I understand photography to quite basic terms, and maybe this is enough to say photography’s contribution Kajzer’s legacy. Photography is a phenomenon of transference, yes, but not only—and not mostly—at the level of the informational. With photography, just as light is the medium of the visible, the visible is the medium of the invisible. That the visible should be the medium for the invisible is not more mysterious than that light should be the medium for the visible at all. (How much do we really grasp the balance of the mind's place and the world's place in our perceptions, or what we call the given, and how well should we trust that the sight of things has somehow risen up from the obscurities?) There are certain subjects—genocide among them—that precisely demand the medium’s plural and contrary mediumism.

Lärche

Lärche

Lärche

Lärche

Lärche

5. Of what happened while photographing in Lower Silesia in 2023, I wrote it to the muse like this:

“the riese sites were typical of most of the holocaust sties i worked in for alive and destroyed—completely unmarked, except for one which was misleadingly marked, some claimed by natural bio systems and illegible as historical sites at all, some overbuilt with new pedestrian uses. so it was something like the kind of work i’ve learned over years to do, which i have no name for, other than to write a sentence as a name: to receive genocide in time, where it happened, is to solicit the visible for its share in the vanished, and to trust that the vanished will appear again, differently, with a metaphoric approach to the visible—the visible not merely as the self-presentation of whatever is seeable, but as the invisible in a substitutional form. (gevalt, i’m afraid in one sentence i’ve tripped over myself seven times, maybe more, almost a slapstick of french literary theory.) anyway, yesterday such photographing lasted a dozen hours or more.”

Wolfsberg

Wolfsberg

Wolfsberg

Wolfsberg

Wolfsberg

6. A few days after I returned to Crete from Poland, ruminating on the trip, I wrote this to the muse:

"i began my day today with a meditation on a poem by avrom sutzkever called “granite wings,” which speaks a vision of cold granite wings sunken into the earth, belonging to some body below, attached by “earth chains” which serve, or function not only to bind wing to body but to bear witness to the existence of the earth-subsumed body, though the poet is careful to note that their witness cannot speak, cannot make testimony. there are, he sees, other witnesses for that, also buried, but “outside the world”—and he speaks of these other witnesses as creatures whose distinguishing mark is to crave words, new words. the granite wings are not inert. they can move, in response to the “non-death” of the body below them. the “non-death” seems to mean something other than life. the poet says clearly what that non-death is: a soul crushed between the pincers of bony pliers—another translation might have rendered it as bone pliers. the body subsumed in earth—maybe we can say wholly of earth at this point—is a soul pressed to crushed but not to death by bony pressure—the image is of a nerve pressed to insensitivity but not destroyedness. this soul-body, somehow, moves, and this movement is received by the granite wings as a shiver, but a shiver coming from above, not from below. when the soul-body moves, the wings receive from above what the poet calls a “sun-shower”—light as rain, light that soaks into granite, penetrates through and through, and the image is of the streaks and striations that are visible in the stone. the wings begin to move, the poet reports, like something returned from the dead in spring. they wrench themselves from the earth, loosen themselves from the earth chains, and take flight coated in “dusty green”—the green, perhaps, of ashes. the poet asks where they are flying, and then answers his own question—there is no knowing or saying a destination, or whether there is a destination. but he promises himself that if he knew where, he would follow—on foot, taking with him his one body “coated in dusty green.”

the profundity of this poem was enough to last me through this day. maybe it was in part that it spoke powerfully to the places in lower silesia. i saw no granite wings in those many camps, but my photographs i think discerned some."

Schotterwerk

Schotterwerk

Schotterwerk

Schotterwerk

Schotterwerk

7. In Plunder, Kaiser writes poignantly on the differences between Kajzer as myth and Kajzer as man. In Poland, he is revered among the treasure hunters and explorers, not for humanistic or ethical or spiritual reasons concerning genocide and its memory, but for the crumbs of information Kajzer provides about Riese—information incidental to Kajzer’s reasons for writing. In Israel, where Kajzer died in 1979, he was an ordinary person—“…just another survivor from Poland,” writes Kaiser, “…childless, remembered by a rapidly diminishing number of people.” And Kaiser trenchantly asks: “Which is preferable? The celebrated myth, which is at least partly false? Or the uncelebrated person, the memory of whom so quickly disappears?”

Abraham Kajzer—to put it starkly—cannot be recuperated either from his myth or from his obscurity. His book is an index and not a guide to the worst days of his life, and reading sympathetically means not entertaining the illusion that we know what those days were, or were to him, just as the finger pointing to the moon should not be mistaken for the moon itself. Likewise, to photograph in the places where Kajzer once passed those days is, at most, to unclose a new space for Kajzer’s opacity, and—if I am allowed to wish—to make a foil for the returning glint of the souls whose paths he crossed.

Dörnhau

Dörnhau

Dörnhau

Dörnhau

Dörnhau

7 + 0. Photography’s native realm is error—to appropriate an elegant formulation by the philosopher John T. Lysaker—photography is born there and error is where it lives.* And if so: then to return to Kajzer’s sites eighty years later and to make photographs that would vibrate with his words, somehow dilate them, even illuminate them from the side of the future—the audacity of such error is not photography’s poetic license, but its poetic trust.

* See John T. Lysaker, “Being True, Sounding False,” European Journal of American Studies, 15-1, 2020.

Erlensbuch

Erlensbuch

Erlensbuch

Erlensbuch

Erlensbuch

Gross-Rosen

Gross-Rosen

Gross-Rosen

Gross-Rosen

Gross-Rosen

Osówka

Osówka

Osówka

Osówka

Osówka

Osówka

Jason Francisco, Chania, 2023