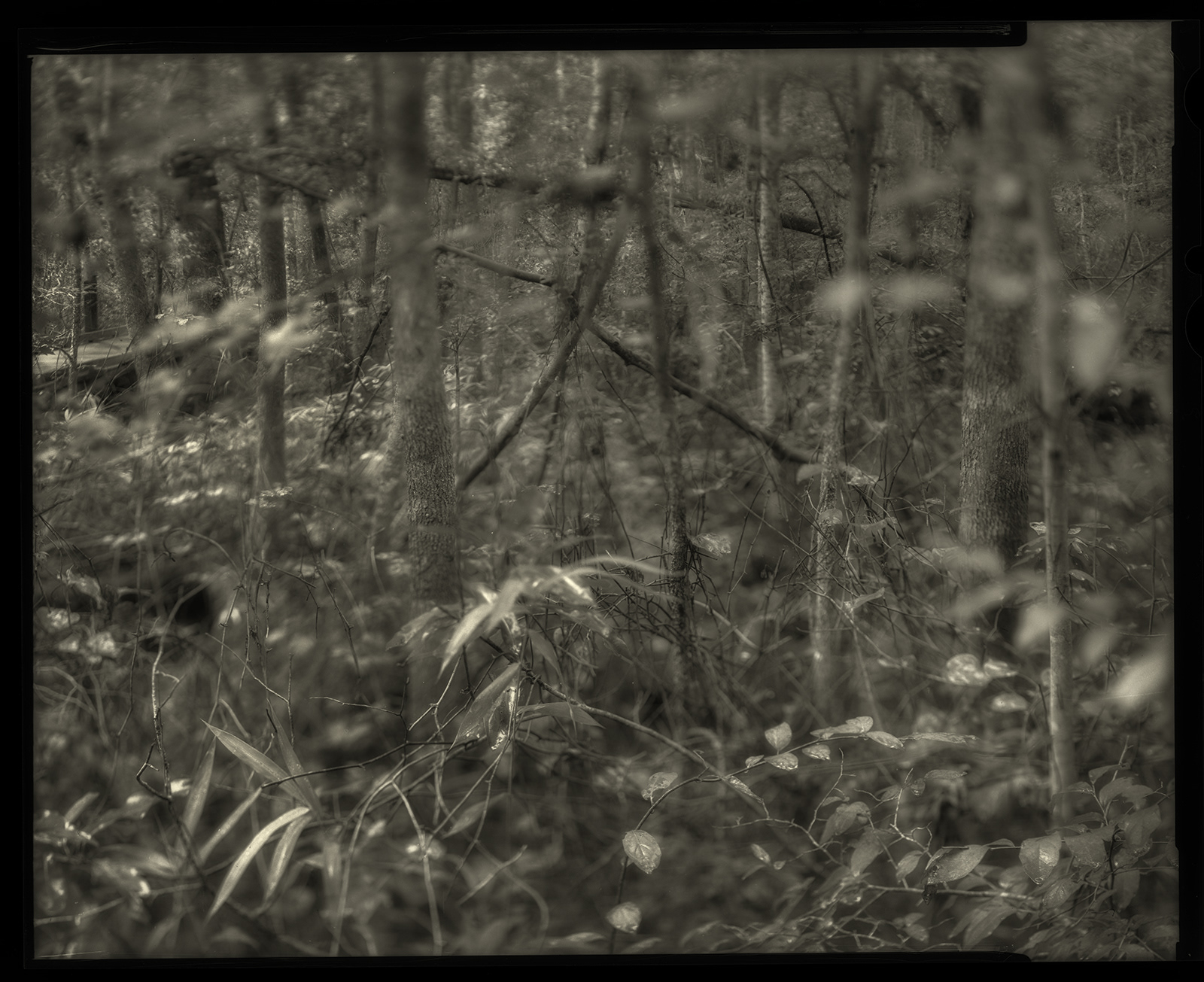

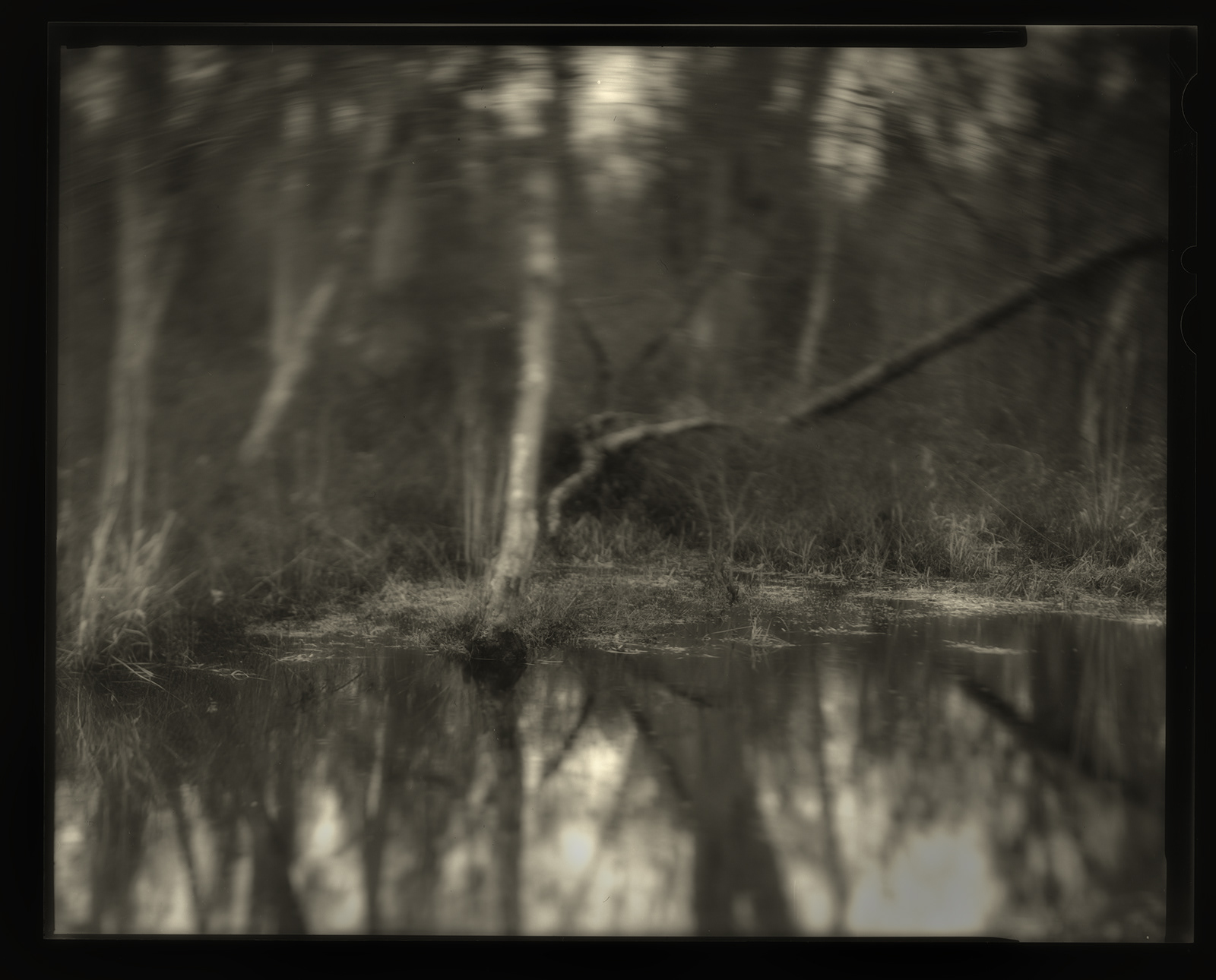

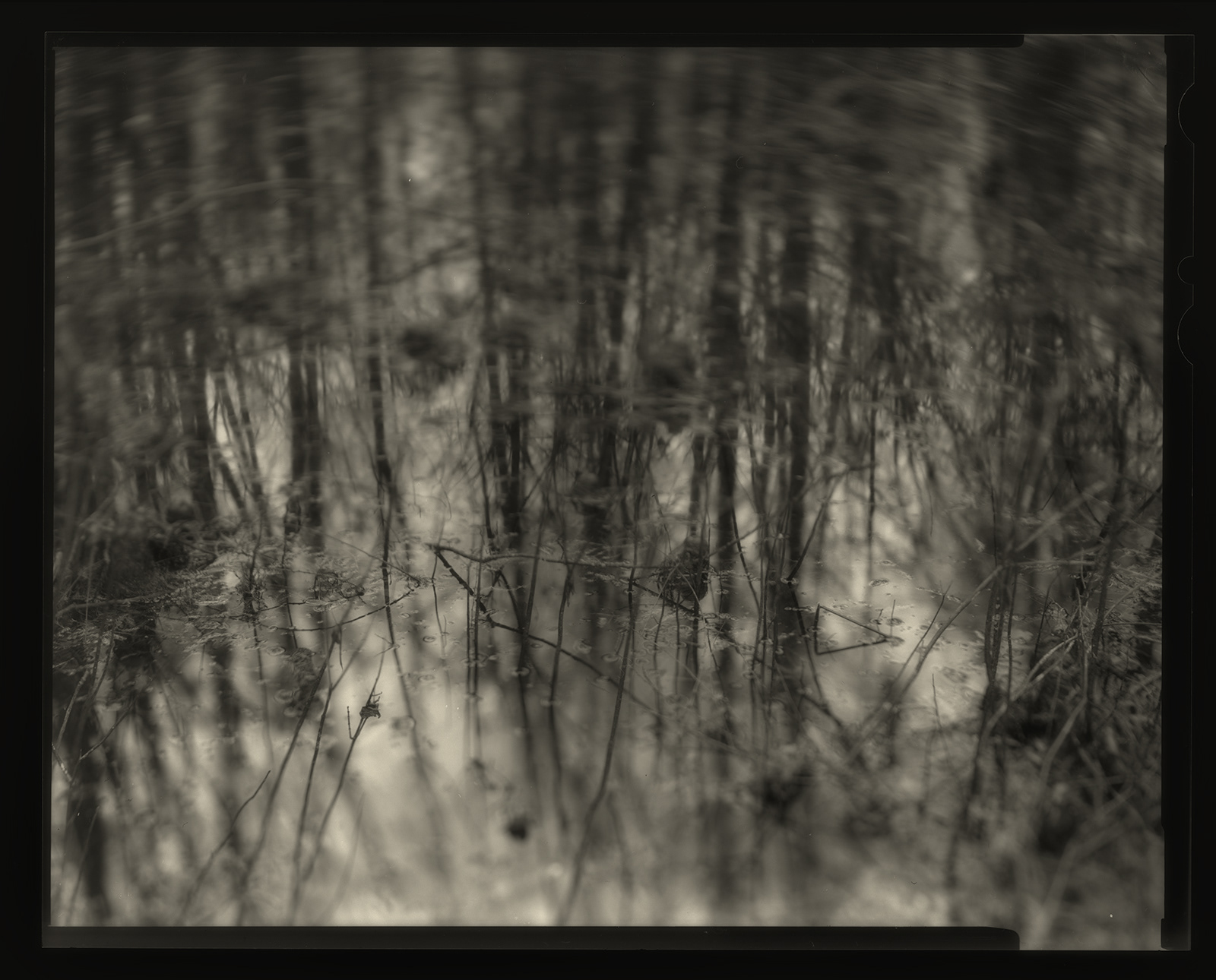

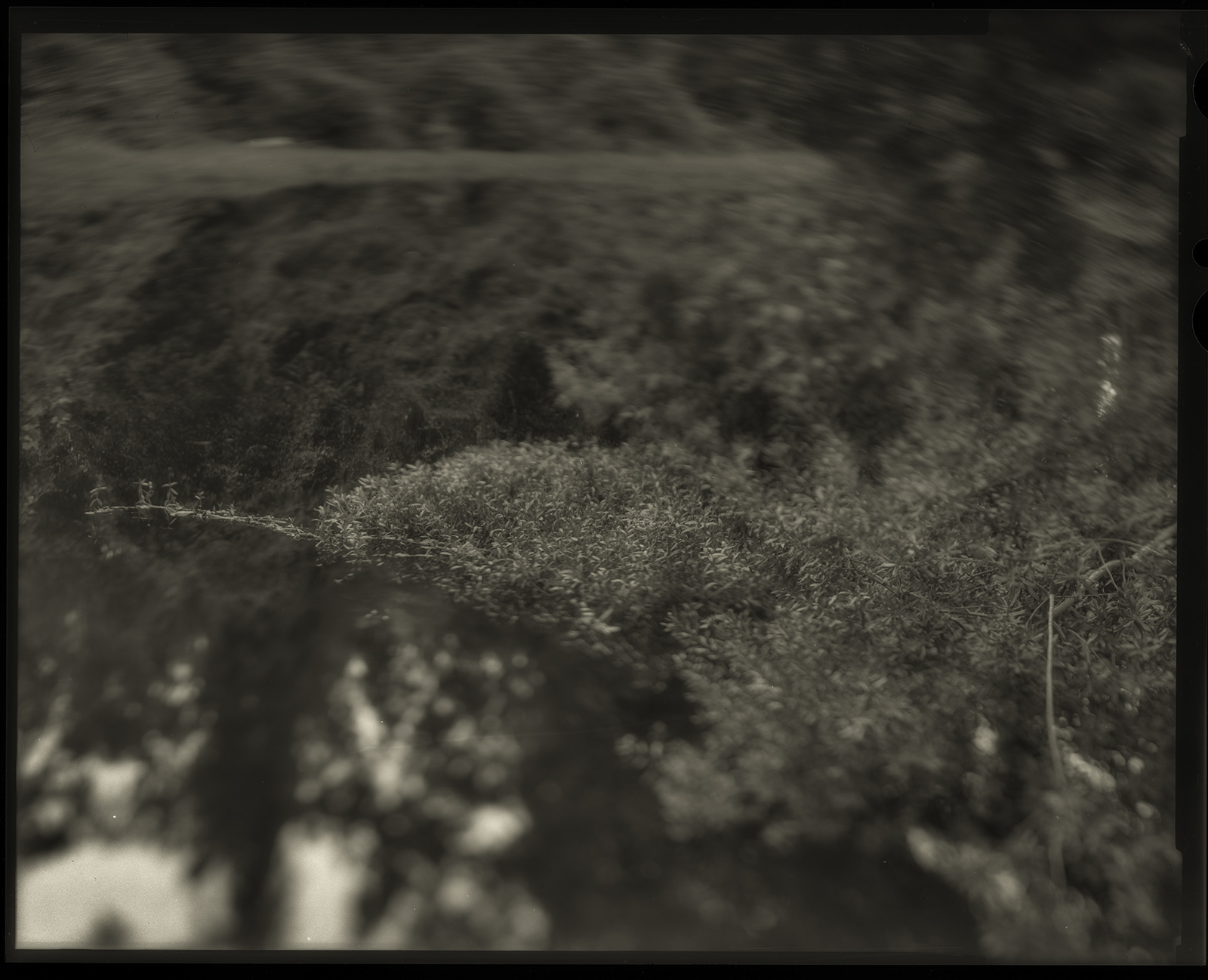

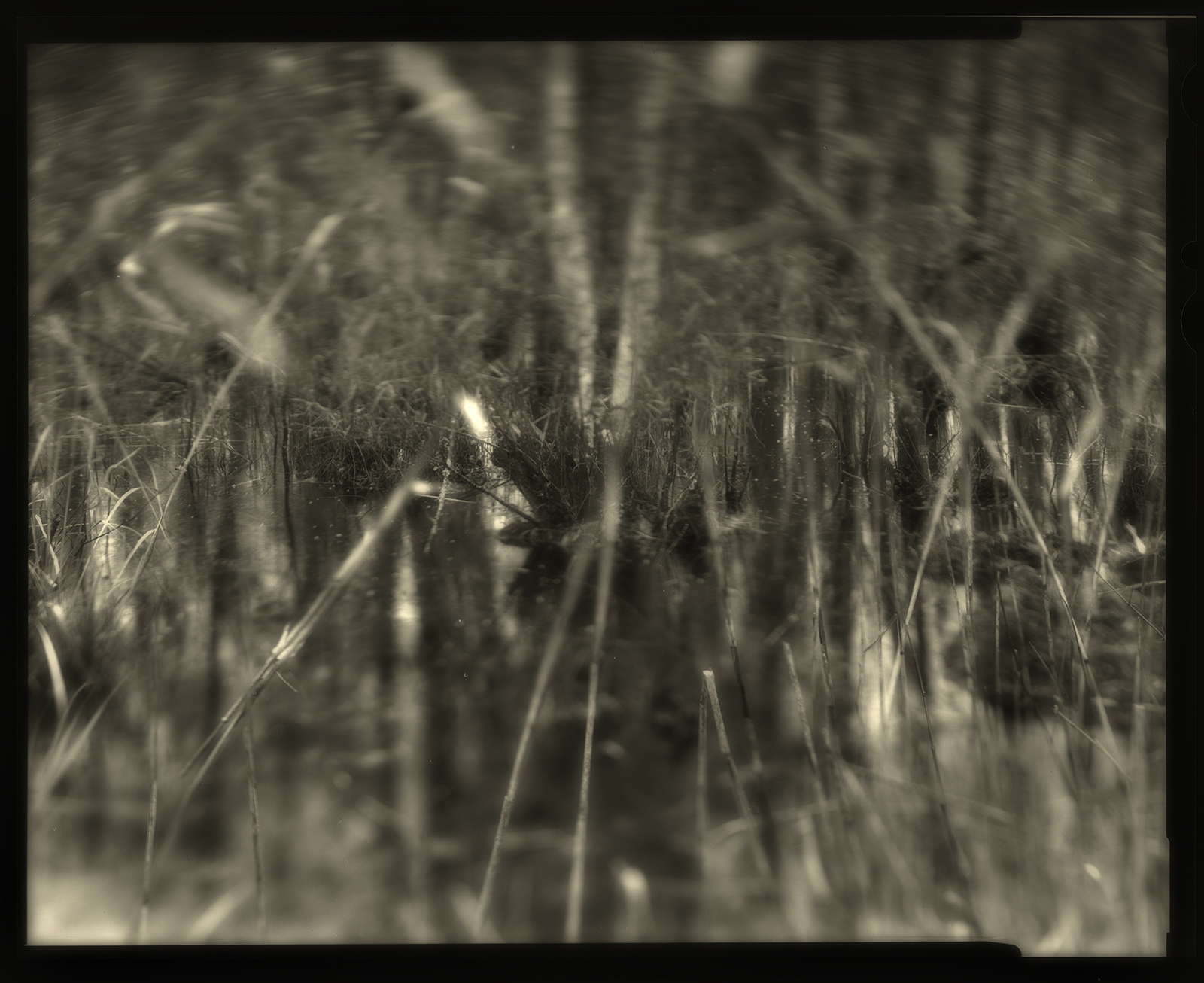

Jason Francisco, Great Dismal Swamp, 2020

The reader who consults the map will discover that the whole eastern shore of the Southern States, with slight interruptions, is belted by an immense chain of swamps, regions of hopeless disorder, where the abundant growth and vegetation of nature, sucking up its forces from the humid soil, seems to rejoice in a savage exuberance, and bid defiance to all human efforts either to penetrate or subdue. These wild regions are the homes of the alligator, the mocassin, and the rattle-snake. Evergreen trees, mingling freely with the deciduous children of the forest, form here dense jungles, verdant all the year round, and which afford shelter to numberless birds, with whose warbling the leafy desolation perpetually resounds. Climbing vines, and parasitic plants, of untold splendor and boundless exuberance of growth, twine and interlace, and hang from the heights of the highest trees pennons of gold and purple,—triumphant banners, which attest the solitary majesty of nature. A species of parasitic moss wreaths its abundant draperies from tree to tree, and hangs in pearly festoons, through which shine the scarlet berry and green leaves of the American holly.

—Harriet Beecher Stowe, 1856

It is 2020, or some similar combustive year bursting forth from the centuries. I am in the Great Dismal Swamp, on the North Carolina side, having traveled southward through the Virginia coastal plain, along the small roads that link the Chesapeake Bay and the Albemarle Sound. I am in the swamp and I am trudging, moving indelicately, sweating profusely. I am carrying a nineteenth-century style camera, a heavy tripod and a bag of lenses and holders and gear. I am a figure of slow mobility, prey for bugs and for curses that spill from my own mouth. The Great Dismal Swamp: once a million acres stretching from Norfolk to Edenton, today hemmed into an officially designated Wildlife Refuge and State Park—22 square miles of forested wetland. The remnant has been declared a National Landmark, but my reasons for coming are the opposite of declarative. For some time I have been reading about the swamp’s social history, which is closely linked to its ecology—a chapter of U.S. history that remains obscure, and precisely so. What we cannot say, think, see about this history was its very reason for being.

From the early seventeenth century until after the American Civil War, more than 250 years, the Great Dismal Swamp was home to societies of African Americans who fled and escaped enslavement. Known as maroons and their way of life as marronage, they made an advantage of the swamp’s natural forbiddingness—vegetation far too thick for horses and boats, intense heat and humidity, teeming with mosquitoes and snakes, not to mention alligators and bears, and at one time also panthers. The severity of life in the swamp provided a foolproof means of self-exile. The swamp’s mire and mudholes and thorns presented an escape from white society—precisely its inhospitality offered a chance to create Black autonomy, and meaningful freedom from white society’s dehumanization, brutality and exploitation. In the swamp, formerly enslaved people created a lifeworld, actually several. Some maroon societies lived deep in the swamp’s hinterlands, and some on the swamp’s borderlands. Some built elevated dwellings and some lived in expertly hidden dugouts. Some lived by farming and raising animals, some returned regularly by nightfall to receive the clandestine assistance of plantation slave communities, some lived by stealth raids on plantations. But unlike runaways, maroons were not seeking temporary relief from plantation life, or passage to non-slaveholding states. Rather they sought a form of permanent freedom while remaining in a slaveholding political regime.

A complex economy particular to the swamp complemented maroons’ relationships to the plantations, and contributed to the feasibility of marronage. Beginning in 1763, the young George Washington, having been elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses after his military career in the French and Indian War, made development of the Great Dismal Swamp one of his central political projects. He founded two syndicates to buy swampland, drain it, convert it to farmland and resell at a large profit, in the meantime harvesting its trees. Washington’s companies oversaw the building of a network of canals—including the Dismal Swamp Historic Canal, begun in 1793 and completed in 1805 (and still in use)—but plans to drain the swamp completely never materialized. Instead, a timber economy developed in tandem with canal excavation, focusing especially on the production of cedar and juniper shingles, supplying towns and cities up and down the eastern seaboard. The swamp’s particular economy brought together a unique mixture of peoples and types of labor. Slaves from nearby plantations worked along free Blacks and also poor whites, in relatively permanent labor communities on the swamp’s perimeter. Maroons were consistently brought in as unofficial workers, surreptitiously joining work companies, paid in kind (not in cash) and given access to food, tobacco and clothing provided by the company. Overall, maroon life relied on intricate systems of communication, surveillance and exchange within an overall framework of mortal danger.

How many people lived in maroon societies in the Great Dismal Swamp? We cannot say precisely. In 1850, Frederick Douglass told of “uncounted numbers of fugitives”—probably the most accurate description we have—and contemporary scholars estimate several thousand prior to the Civil War, making the swamp the largest site of marronage in North America. How many people thrived in the swamp and how many merely suffered it—enduring hunger, malnutrition, exposure, lack of sunlight, insufficient medical attention? How many moved on from the swamp, traveling north to freedom on the Underground Railroad? How many returned to plantation life? How many chose slow death in the bogs rather than resubmitting to bondage? We have no answers to these questions. We do know something of the stakes in choosing marronage, at least by way of the punishments and retribution that maroons faced if captured or returned. These included branding on the face, castration, cutting of the ears and the Achilles tendon, splitting of the feet with knives, and most of all, whippings—sadistically inflicted, including the pouring of salt, red pepper, vinegar and turpentine in the lacerations. How many people suffered the tortures and retributions inflicted on fugitive slaves we do not know.

By the mid-nineteenth century, maroon life was an item of popular culture, which is not to say it was well seen. In 1842, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published “The Slave in the Dismal Swamp,” an anti-slavery poem meant to stir the abolitionist cause. “In dark fens of the Dismal Swamp / The hunted Negro lay;” begins Longfellow’s plaint, which goes on to describe maroons in the generic terms of Christian pity—poor, crouching, scarred, doomed. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s second novel, Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp, published in two volumes in 1856, sold over 100,000 copies in its first month. Dred’s title character is a Black revolutionary, a composite of Denmark Vesey and Nat Turner, enslaved men who plotted and led well-known revolts. If the novel is striking for its moral courage—in his righteous anger, Dred is presented as the heir to the American revolution, and the novel mounts a careful indictment of slavery as a system of laws, what today would be called institutional racism—it is also striking for the stereotypes it does not break. Familiar (ugh, still familiar) tropes of Black savagery and docility remain defining aspects of the novel’s characters, drawn in special relief by the negative terms in which white society saw the swamp: as dreary, dismal, wild. But more to the point is that Stowe’s Dred is no longer much read. It is eclipsed in literary memory by her earlier book, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which approaches slavery not by way of systemic critique, but the study of individual temperament, akin to contemporary approaches to racism limited to personal psychology. Stowe’s abolitionism evolved to a vision of armed Black rebellion as it met legalistic denunciation of racial injustice—a combination that is still a challenge to the mainstream American psyche.

Today, the swamp’s history is not a subject of popular culture at all, either new or reclaimed. I know of no novels or films that depict it. The antebellum swamp’s social history is now the province of historians, for example Sylviane A. Diouf’s Slavery’s Exiles, the source of the information above on punishments, which ably if academically addresses the swamp as a “site of empowerment, migrations, encounters, communication, exchange, solidarity, resistance, and entangled stories.” Daniel Sayers’ A Desolate Place for a Defiant People, from which my brief comments about labor organization above are drawn, is likewise a careful exposition of the historical and archaeological record. These works follow from historical non-fictional accounts of life in the swamp, most importantly Frederick Law Olmsted’s 1856 book, Journey in the Seaboard Slave States, which contains detailed descriptions of the swamp’s economy, and transcriptions of interviews with Black lumbermen, free and slave.

And artists? Did they and do they have something to contribute to the understanding of historical memory of marronage in the Virginia/North Carolina coastal plain? Nineteenth century visual culture does include depiction of maroon life. A series of illustrations by David Hunter Strother, known also by his pen name Porte Crayon, followed the artist’s excursion into the swamp. Appearing in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in September 1856, his work includes what seems the only example of a portrait of a maroon published in a national magazine. Identified as “Osman,” the sketch shows a man nearly encircled by vines and bramble, not quite stepping through it nor camouflaged within it, one hand palming what seems a wild bird, the other cradling a rifle. The fact of the gun alone indicates a network of survival, from which he procured a supply of ammunition. By contrast, David Edward Cronin’s 1888 painting “Fugitive Slaves in the Dismal Swamp, Virginia” is entirely a work of the studio, a romantic exercise in historical memory made in the context of the post-bellum South. By the time Cronin made his image, marronage had mostly already ended, and slavery had been replaced by the Jim Crow system of legalized discrimination and disenfranchisement, and the Klan-driven system of extralegal vigilante terror and murder.

David Hunter Strother, also known as Porte Crayon, "Osman," from "The Dismal Swamp," Harper's New Monthly Magazine, (September 1856), pp. 441-455.

David Edward Cronin, “Fugitive Slaves in the Dismal Swamp, Virginia," Library Company of Philadelphia.

It is 2020, and the struggle for racial justice has erupted again in the streets of America. This year, the centuries have churned forth a broad coalitional demand for an end to police brutality, reparations for Black Americans, and a wholesale anti-racist cultural reconstruction. I have been in the streets as a non-Black ally of the movement, and from the streets I have gone to the swamp, all but certain that later I will be back in the streets. Giving-image to the streets is one set of challenges, and giving-image to the swamp seems its counterpart, in several senses.

Jason Francisco, Movement for Black Lives, Atlanta 2020

Jason Francisco, Movement for Black Lives, Atlanta 2020

Jason Francisco, Movement for Black Lives, Atlanta 2020

By way of historical memory, it seems to me that the least the maroons deserve is that we respect the fundamental terms of their freedom: they deserve that we honor their opacity. They produced that opacity skillfully and diligently, essentially as an art of alienation that made an asset of the swamp’s minatory ecology and that learned brilliantly to navigate the periphery of white institutional power. They deserve that we honor the core terms of their survival, namely subversive self-concealment. In its own time, their freedom was precisely misaligned with what outsiders could observe, and in historical time, the swamp has swallowed their freedom, leaving it nowhere to be seen. And here the swamp and the street emerge as sites of mutual resistance in the movement for racial justice, the latter entirely directed toward visibility and seenness. And, too, the history of the maroons does not fit neatly into the contemporary—and badly needed—work of undoing the erasure of Black culture, inasmuch as erasure was for the maroons a tool of liberation, not its antithesis.

Respecting the basic terms of the maroons’ accomplishment suggests to me that we turn to loss as the appropriate medium of encounter—loss of clarity, loss of certainty, loss of information and loss of the expectation of information. Encounter: not the kind of knowing based on acquisition and possession of fact or explanation or image, rather the kind of knowing based in release from the compulsion to possess. Encounter: not the hunt for verities and verifications and avowals, rather a receptivity to inference, conjecture and tentative sighting. Encounter: not the imperative to claim understanding as if it were the spoils of truth-capture, rather the willingness to allow understanding the dimensional presence of ambiguity and mutability.

Photography, of course, is a medium strongly aligned with the carceral urges of modernity—the collective wish for a visual medium that captures, holds-captive, maintains-in-captivity what it shows. I feel myself subject to this type of photography when I use my hand-held digital camera—the one I use in the streets—to photograph in the swamp.

Jason Francisco, Great Dismal Swamp, North Carolina, 2020

Jason Francisco, Great Dismal Swamp, North Carolina, 2020

Jason Francisco, Great Dismal Swamp, North Carolina, 2020

Jason Francisco, Great Dismal Swamp, 2020

Jason Francisco, Great Dismal Swamp, 2020

The black and white photographs I make with the large, contemplative camera begin to move the terms of knowing to a different field of reference—toward loss, opacity and inconclusivenss as the basis for historical memory of the maroons. These photographs, as I want them, do not attempt to recover or recuperate that memory. If they resolve nothing about how maroons lived, I will count it as an accomplishment. If they fail to fit or retrofit historical consciousness to acts of observation—fail to allow historical consciousness to know itself through pictures—I will likewise count that as an accomplishment. The maroons deserve an extra-representational art, and a post-representational understanding of photography as such an art. For me, this means well-unmade pictures, well-seen and dis-composed in their movements of blur and sharpness and a simultaneously dense and open rendition of spatial depth. The gliding frictions in these photographs are not a visual language for the maroons’ lives or their freedom—their freedom has no such language that we can learn, that welcomes and assures us—but if these pictures can prompt questions about what those lives and that freedom meant, I will count it as an accomplishment.

It is 2020, and I do not know how to remember 1620 in the swamp, or any earlier year. Time has made the maroons’ escape even more radical. The swamp seems as inhospitable as it ever was, and in this sense suggests a deflective encounter with slavery—being there, you get a sense of what miseries were preferable to enslavement—but ultimately, I feel that maroon life has no likeness. No story and no image can do more than brush by the maroons’ own freedom, whatever it was. My sense of their liberty is as obnubilated as the swamp itself, and the best I can do is make images that un-capture the imagination of that liberty. I myself, an American in my own time, am not at liberty to stop seeking the image of freedom. Not at liberty: the maroons in their freedom are a blessing in memory, and we ourselves deserve a freedom of memory true to their enigma in all its skill.

Jason Francisco

March 2021