Traces of Memory: A Contemporary Look at the Jewish Past in Poland

A Permanent Exhibition at the Galicia Jewish Museum, Kraków, Poland

A Permanent Exhibition at the Galicia Jewish Museum, Kraków, Poland

Notes on a Posthumous Collaboration

Jason Francisco

The pictures in this gallery are the result of an unusual triple collaboration. Their touchstone is a collaboration between Jonathan Webber, the social anthropologist and historian who wrote the accompanying texts, and the photographer Chris Schwarz (1948-2007), founder and first director of the Galicia Jewish Museum in Kraków. Their collaboration lasted more than a decade, beginning in the early 1990s, and resulted in the core exhibition of the Museum, Traces of Memory: A Contemporary Look at the Jewish Past in Poland. On a secondary level, the pictures here reflect a similar collaboration between Dr. Webber and me in 2015-2016, when we created an updated version of that exhibition, currently on view in the Museum. Finally, this work represents a collaboration between Schwarz and me––what could be called a posthumous collaboration.

Actually this project represents the second of two posthumous collaborations I have undertaken with Chris Schwarz. From 2014-2016 the Galicia Jewish Museum showed my exhibition An Unfinished Memory: Jewish Heritage and the Holocaust in Eastern Galicia, for which I was photographer, writer, designer, curator, and researcher. An Unfinished Memory considered the contemporary meanings of the Jewish past in the eastern half of the historical province of Galicia, today in western Ukraine––something Traces of Memory does not address. My task with An Unfinished Memory was to build on Traces of Memory but not duplicate it intellectually or aesthetically, as appropriate to the differences between contemporary Ukraine and Poland vis à vis Jewish history. As a companion exhibition, it formed an indirect collaboration with Schwarz’s work.

When the Galicia Jewish Museum approached me in 2014 to undertake an updating of Traces of Memory, the proposal was to make photographs that would be directly integrated into Schwarz’s work. The new pictures would reflect important physical changes in Jewish material and architectural patrimony in Polish Galicia, and new developments in Polish memory culture concerning the Jewish past. I was prepared for this task, inasmuch as I had already traveled and photographed extensively in Polish Galicia for a separate project, Alive and Destroyed: A Meditation on the Holocaust in Time, a work whose themes partially overlap Traces of Memory and An Unfinished Memory.

From the beginning, all of us closely involved in the Traces update––Dr. Webber, me, Jakub Nowakowski (director of the Galicia Jewish Museum), Tomasz Strug (the Museum’s deputy director and head curator), and Anya Wencel (the Museum’s education director)––wrestled with the hazards of the task at hand. We all understood that we were breaking or breaking-into the integrity of a mature artist’s work, arguably his finest work. As a photographer, I especially understood what that integrity consists of. I know from the inside that the art of documentary photography demands all the intellectual engagement, emotional courage, and aesthetic curiosity that any artistic practice demands. In addition, it requires a special responsiveness to that which the artist precisely does not invent––the actualities of the world itself––and it involves a hard-won working method made of improvisation and discipline in equal parts, capable of courting luck, probing circumstance, and stubbornly negotiating with visual possibilities large and small. From the first time I saw Traces of Memory in 2010, it was obvious to me that this was a project built painstakingly over many years, resulting in a work of great conceptual and aesthetic harmony. That harmony induces a certain contemplative focus––I have felt it myself and seen it over and over while watching visitors to the Museum––namely a prolonged, searching encounter with the past and the future by way of the surfaces of the present. In the best of Schwarz’s pictures, there is a sense of reckoning with the preciousness and vulnerability and resilience and enduringness of the Jewish in Poland, all of these at once.

Jason Francisco

The pictures in this gallery are the result of an unusual triple collaboration. Their touchstone is a collaboration between Jonathan Webber, the social anthropologist and historian who wrote the accompanying texts, and the photographer Chris Schwarz (1948-2007), founder and first director of the Galicia Jewish Museum in Kraków. Their collaboration lasted more than a decade, beginning in the early 1990s, and resulted in the core exhibition of the Museum, Traces of Memory: A Contemporary Look at the Jewish Past in Poland. On a secondary level, the pictures here reflect a similar collaboration between Dr. Webber and me in 2015-2016, when we created an updated version of that exhibition, currently on view in the Museum. Finally, this work represents a collaboration between Schwarz and me––what could be called a posthumous collaboration.

Actually this project represents the second of two posthumous collaborations I have undertaken with Chris Schwarz. From 2014-2016 the Galicia Jewish Museum showed my exhibition An Unfinished Memory: Jewish Heritage and the Holocaust in Eastern Galicia, for which I was photographer, writer, designer, curator, and researcher. An Unfinished Memory considered the contemporary meanings of the Jewish past in the eastern half of the historical province of Galicia, today in western Ukraine––something Traces of Memory does not address. My task with An Unfinished Memory was to build on Traces of Memory but not duplicate it intellectually or aesthetically, as appropriate to the differences between contemporary Ukraine and Poland vis à vis Jewish history. As a companion exhibition, it formed an indirect collaboration with Schwarz’s work.

When the Galicia Jewish Museum approached me in 2014 to undertake an updating of Traces of Memory, the proposal was to make photographs that would be directly integrated into Schwarz’s work. The new pictures would reflect important physical changes in Jewish material and architectural patrimony in Polish Galicia, and new developments in Polish memory culture concerning the Jewish past. I was prepared for this task, inasmuch as I had already traveled and photographed extensively in Polish Galicia for a separate project, Alive and Destroyed: A Meditation on the Holocaust in Time, a work whose themes partially overlap Traces of Memory and An Unfinished Memory.

From the beginning, all of us closely involved in the Traces update––Dr. Webber, me, Jakub Nowakowski (director of the Galicia Jewish Museum), Tomasz Strug (the Museum’s deputy director and head curator), and Anya Wencel (the Museum’s education director)––wrestled with the hazards of the task at hand. We all understood that we were breaking or breaking-into the integrity of a mature artist’s work, arguably his finest work. As a photographer, I especially understood what that integrity consists of. I know from the inside that the art of documentary photography demands all the intellectual engagement, emotional courage, and aesthetic curiosity that any artistic practice demands. In addition, it requires a special responsiveness to that which the artist precisely does not invent––the actualities of the world itself––and it involves a hard-won working method made of improvisation and discipline in equal parts, capable of courting luck, probing circumstance, and stubbornly negotiating with visual possibilities large and small. From the first time I saw Traces of Memory in 2010, it was obvious to me that this was a project built painstakingly over many years, resulting in a work of great conceptual and aesthetic harmony. That harmony induces a certain contemplative focus––I have felt it myself and seen it over and over while watching visitors to the Museum––namely a prolonged, searching encounter with the past and the future by way of the surfaces of the present. In the best of Schwarz’s pictures, there is a sense of reckoning with the preciousness and vulnerability and resilience and enduringness of the Jewish in Poland, all of these at once.

Chris Schwarz, Interior of the Łańcut synagogue, from Traces of Memory

Changing the exhibition raised difficult questions about how documentary pictures do and do not age. Like the work of all good documentarians, Schwarz’s pictures operate simultaneously on two levels––the informational and the poetic. None are mere visual records, and none pretend to an impersonal or factographic perspective. For this reason, even when things have changed enough to make his pictures informationally inaccurate, his pictures often remain affectively and spiritually accurate. For example, his photograph of the unrenovated synagogue at Rymanów––one of his masterpieces and one of the signature images of the original Traces of Memory––does not represent the physical state of the building today, or the forces of cultural reclamation responsible for the building’s restoration. Still, apart from its historic value, the image powerfully evokes myriad Jewish sites that are still ruined, and so remains true to the broader realities of Jewish loss in post-Holocaust and post-Communist Poland. Given that photographs can be both accurate and inaccurate, we struggled to find a method to determine which pictures to keep. Gradually a working strategy emerged: to retain those pictures by Schwarz that remained both informationally and poetically fair to the subject a decade after the Museum opened, as for example his picture of the Łańcut synagogue, reproduced above; to retain those pictures of particular poetic importance (and to attempt to redeem the informational problems though textual revision); to replace those pictures whose informational deficiencies outweighed other factors; to add new photographs for newly emerged subjects that Schwarz did not or could not photograph in the first place.

Thus the core demand of this particular posthumous collaboration was to make new pictures that could be seamlessly integrated into Schwarz’s accomplishment, and that remained true to my own sensibility. The differences between Schwarz’s visuality and my own were apparent to me from the beginning. Composed with great visual economy and precision, Schwarz’s pictures are forthright and expository in their approach. His style of visual thinking is pitched toward conceptual clarification, such that his pictures seem to provide answers to predicating questions that we grasp precisely by looking into the images. Inasmuch as the image-text relationship in Traces of Memory is horizontal rather than vertical, i.e. an equal balance in which photographs are more than illustrations for the texts and the texts are more than captions for the pictures, the accompanying texts depend from the outset on the photographs’ having accomplished their expository work well.

My own visual thinking tends to be rather different. My photographs avoid the mode of visual disambiguation, and as a documentarian, I am interested in making pictures (and picture-sequences, and picture-text works) that communicate conceptual irresolution, volatility, and enigma. Partly this difference is aesthetic, in that I tend to compose pictures contrapuntally, with asymmetrical visual design, thereby entering the eye and the mind into a dialectic or relay between multiple “events” within the image. Partly the difference is philosophical, especially with regard to the Jewish past in eastern Europe. Where Schwarz is mostly concerned with exploring the traces of Jewish life that remain, I have been concerned with the dialogue between traces and tracelessness. I tend to see post-Holocaust Jewish ruins first as portals into the problems of rupture, absence and nothingness, and second as vestiges of Jewish historical presence, whereas I think for Schwarz it is just the reverse.

Before beginning my work, I had the benefit of studying Schwarz’s original positives for Traces of Memory. Schwarz made most of his pictures on medium format slide film, using a tripod-mounted Linhof, a camera that allows tilt-shift control; for those involving human figures he used a Leica 35mm camera. I too adopted a two-camera approach, using a 4x5 view camera for pictures of architecture and sites, and a digital Leica for hand-held pictures with human figures. Following Schwarz’s lead, and departing from my own tendencies, I favored center-weighted compositions made with normal focal length lenses (a 135mm and 150mm for the 4x5 camera), and symmetrical compositions when using wide-angle lenses (75mm and 90mm for the 4x5 camera).

Mostly, though, my posthumous collaboration with Chris Schwarz happened not by way of technical confluences, but something harder to name––an inner dialogue I sustained with him as a figure of my imagination (we never had the benefit of meeting before his death) but not from my imagination. Having studied Schwartz’s work carefully, I continuously tested my own responses against my intuition of the way he would have handled various pictorial situations and challenges. Very often I would begin with my own native response to a site, and move in stages toward a photograph that I felt to be touched by Schwarz’s consciousness as I carried it in myself. The best analogy I can make for this experience is the relationship between a writer and a translator, the latter channelling and transfiguring the former, except that in this case, I as translator was responsible for the primary act of creation. I count it as a success if the viewer has trouble distinguishing my pictures in this book from those of Chris Schwarz, and as a greater success if the reader can indeed distinguish them. Voices singing in harmony do, after all, remain discernible and distinct.

The creative momentum I found in two years of working on the update of Traces of Memory yielded far more photographs than the Museum needed, enough to replace the exhibition almost completely. Indeed, my work for the Museum between 2013 and 2016––An Unfinished Memory plus the updated Traces of Memory––looks at the Jewish past in the whole of historical Galicia, Polish and Ukrainian halves alike.

Thus the core demand of this particular posthumous collaboration was to make new pictures that could be seamlessly integrated into Schwarz’s accomplishment, and that remained true to my own sensibility. The differences between Schwarz’s visuality and my own were apparent to me from the beginning. Composed with great visual economy and precision, Schwarz’s pictures are forthright and expository in their approach. His style of visual thinking is pitched toward conceptual clarification, such that his pictures seem to provide answers to predicating questions that we grasp precisely by looking into the images. Inasmuch as the image-text relationship in Traces of Memory is horizontal rather than vertical, i.e. an equal balance in which photographs are more than illustrations for the texts and the texts are more than captions for the pictures, the accompanying texts depend from the outset on the photographs’ having accomplished their expository work well.

My own visual thinking tends to be rather different. My photographs avoid the mode of visual disambiguation, and as a documentarian, I am interested in making pictures (and picture-sequences, and picture-text works) that communicate conceptual irresolution, volatility, and enigma. Partly this difference is aesthetic, in that I tend to compose pictures contrapuntally, with asymmetrical visual design, thereby entering the eye and the mind into a dialectic or relay between multiple “events” within the image. Partly the difference is philosophical, especially with regard to the Jewish past in eastern Europe. Where Schwarz is mostly concerned with exploring the traces of Jewish life that remain, I have been concerned with the dialogue between traces and tracelessness. I tend to see post-Holocaust Jewish ruins first as portals into the problems of rupture, absence and nothingness, and second as vestiges of Jewish historical presence, whereas I think for Schwarz it is just the reverse.

Before beginning my work, I had the benefit of studying Schwarz’s original positives for Traces of Memory. Schwarz made most of his pictures on medium format slide film, using a tripod-mounted Linhof, a camera that allows tilt-shift control; for those involving human figures he used a Leica 35mm camera. I too adopted a two-camera approach, using a 4x5 view camera for pictures of architecture and sites, and a digital Leica for hand-held pictures with human figures. Following Schwarz’s lead, and departing from my own tendencies, I favored center-weighted compositions made with normal focal length lenses (a 135mm and 150mm for the 4x5 camera), and symmetrical compositions when using wide-angle lenses (75mm and 90mm for the 4x5 camera).

Mostly, though, my posthumous collaboration with Chris Schwarz happened not by way of technical confluences, but something harder to name––an inner dialogue I sustained with him as a figure of my imagination (we never had the benefit of meeting before his death) but not from my imagination. Having studied Schwartz’s work carefully, I continuously tested my own responses against my intuition of the way he would have handled various pictorial situations and challenges. Very often I would begin with my own native response to a site, and move in stages toward a photograph that I felt to be touched by Schwarz’s consciousness as I carried it in myself. The best analogy I can make for this experience is the relationship between a writer and a translator, the latter channelling and transfiguring the former, except that in this case, I as translator was responsible for the primary act of creation. I count it as a success if the viewer has trouble distinguishing my pictures in this book from those of Chris Schwarz, and as a greater success if the reader can indeed distinguish them. Voices singing in harmony do, after all, remain discernible and distinct.

The creative momentum I found in two years of working on the update of Traces of Memory yielded far more photographs than the Museum needed, enough to replace the exhibition almost completely. Indeed, my work for the Museum between 2013 and 2016––An Unfinished Memory plus the updated Traces of Memory––looks at the Jewish past in the whole of historical Galicia, Polish and Ukrainian halves alike.

The pictures of mine in these galleries represent a fraction of that larger, integrated project. They appear here a form significantly different than what visitors to the Museum will find, in several senses. First, they are presented here on their own, without the work of Chris Schwarz. Second, they are presented without accompanying texts––neither those of Dr. Webber, nor those I might write. Third, the selection of pictures is significantly different than those hanging in the Museum. Fourth, the organization here does not follow the categorial structure of the exhibition, which divides its subject into five sections, according to Dr. Webber's vision: Jewish Life in Ruins, Jewish Life as It Once Was, Sites of Massacre and Destruction, How the Past Is Being Remembered, The Renewal of Jewish Life Today. Of course, it would be possible to reconstruct these sections as online galleries. Instead, the gallery here integrates work from all five sections, presenting the pictures––my findings, as it were––as phenomena simultaneously occurring across the landscape of Jewish memory in southeastern Poland today. The sequence here can be considered a movement, analogous to a musical composition.

I would like to think that Chris Schwarz would embrace the hunger and ambition that came to me in a deep, sustained response to his work, much as I hope the selection of my photographs here honors and extends his legacy.

Jason Francisco

Kraków, 2017

Interior of the renovated synagogue, Bobowa

Unrenovated synagogue painting of Jerusalem, Bobowa

The Trinczer house, Holocast massacre site, Gniewczyna

New forest tombstone, Jasło. An unusual double gravestone for the Jewish Fisch family and the Polish man who was murdered with them for attempting to rescue them, Jan Jantoń

Visitors studying Jewish history in the streets of Kazimierz, Kraków

Flags in front of the town hall, Kolbuszowa. The European Union and Polish flags fly beside the town flag of Kolbuszowa, whose prewar insignia––still retained despite the annihilation of the Jewish population––affirms Jewish-Polish friendship.

Leon Gawąd, Polish caretaker of the Jewish cemetery, Bochnia. Gawąd is pictured standing by the grave of Josef Frankel, his childhood doctor, and in fact the person who delivered him.

Largely destroyed ancient Jewish cemetery, Lesko

Ruins of the great synagogue, Dukla

Pillaged Jewish graves on the site of the Płaszów camp, Kraków

Interfaith commemoration of the massacres at Zbylitowska Góra

Grave of the Jewish sage Moses Isserles, Kazimerz, Kraków

Interior courtyard of a ruined synagogue, Przemyśl

The ruined synagogue of the village of Stary Dzików

Reconsecrated Jewish cemetery, Brzostek

Public library, formerly the town synagogue, Biecz

Partly renovated synagogue, Cieszanów

Mass grave of Holocaust victims, Kolbuszowa

Ethnographic exhibition, Kraków. Anti-semitic Polish Easter traditions are on view in the city's main ethnographic museum.

Lucky Jews for sale, Kazimierz, Kraków. Images of stereotypically religious-looking Jews holding coins are widely sold and collected.

Holocaust mass grave, Rzepiennik Strzyżewski

Remains of the great synagogue, Tarnów

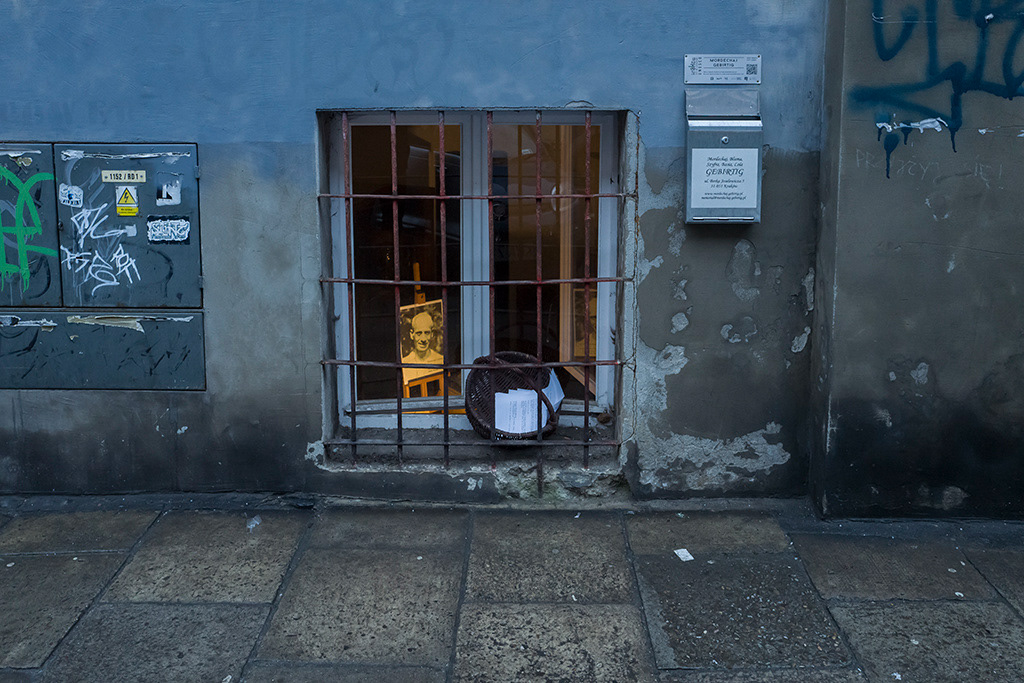

Remembrance of the great Jewish bard, Mordechai Gebirtig, Kazimierz, Kraków

Recovered headstones deposited in the Jewish cemetery, Gorlice

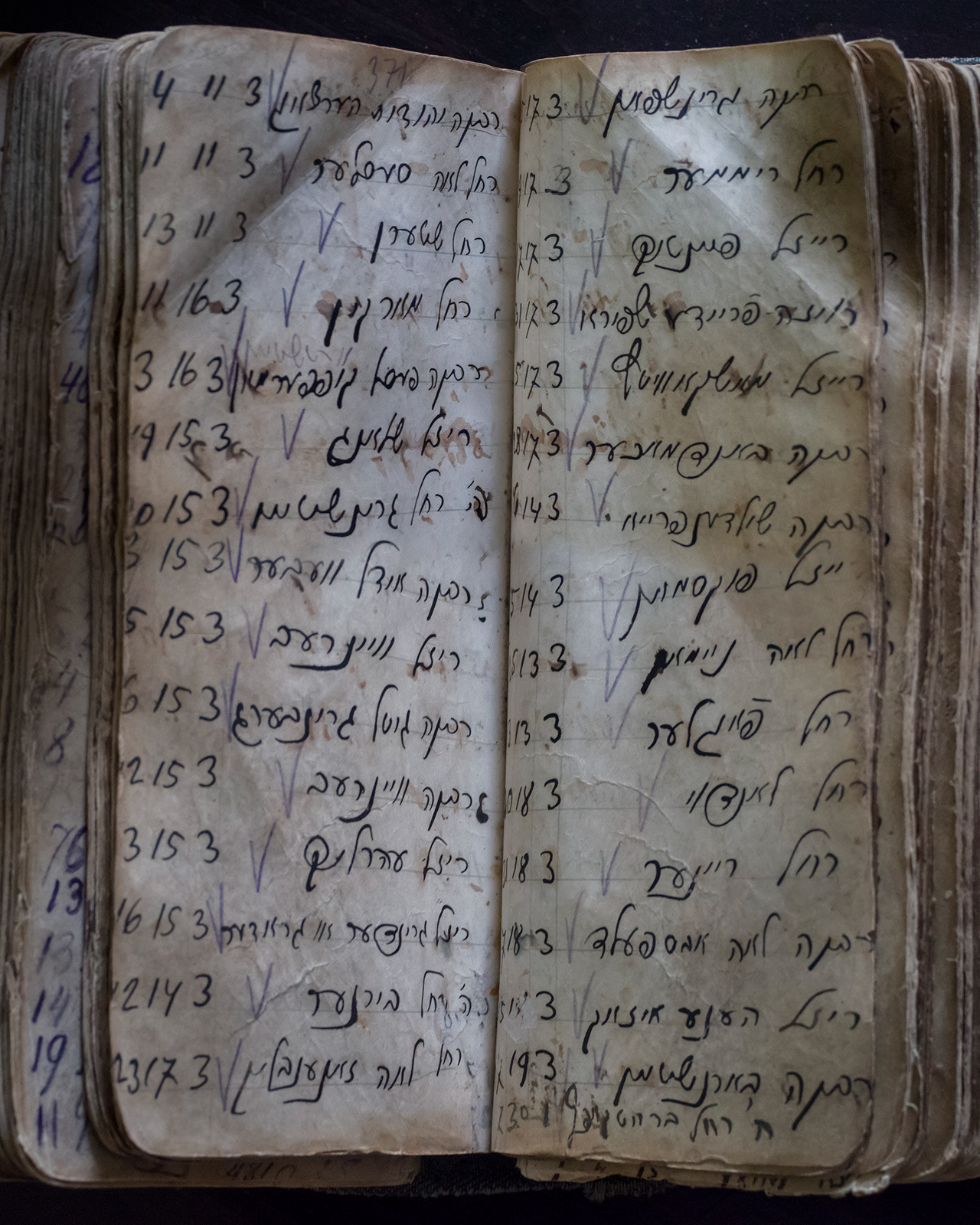

Registry of the destroyed cemetery on the site of the Płaszów camp, Kraków

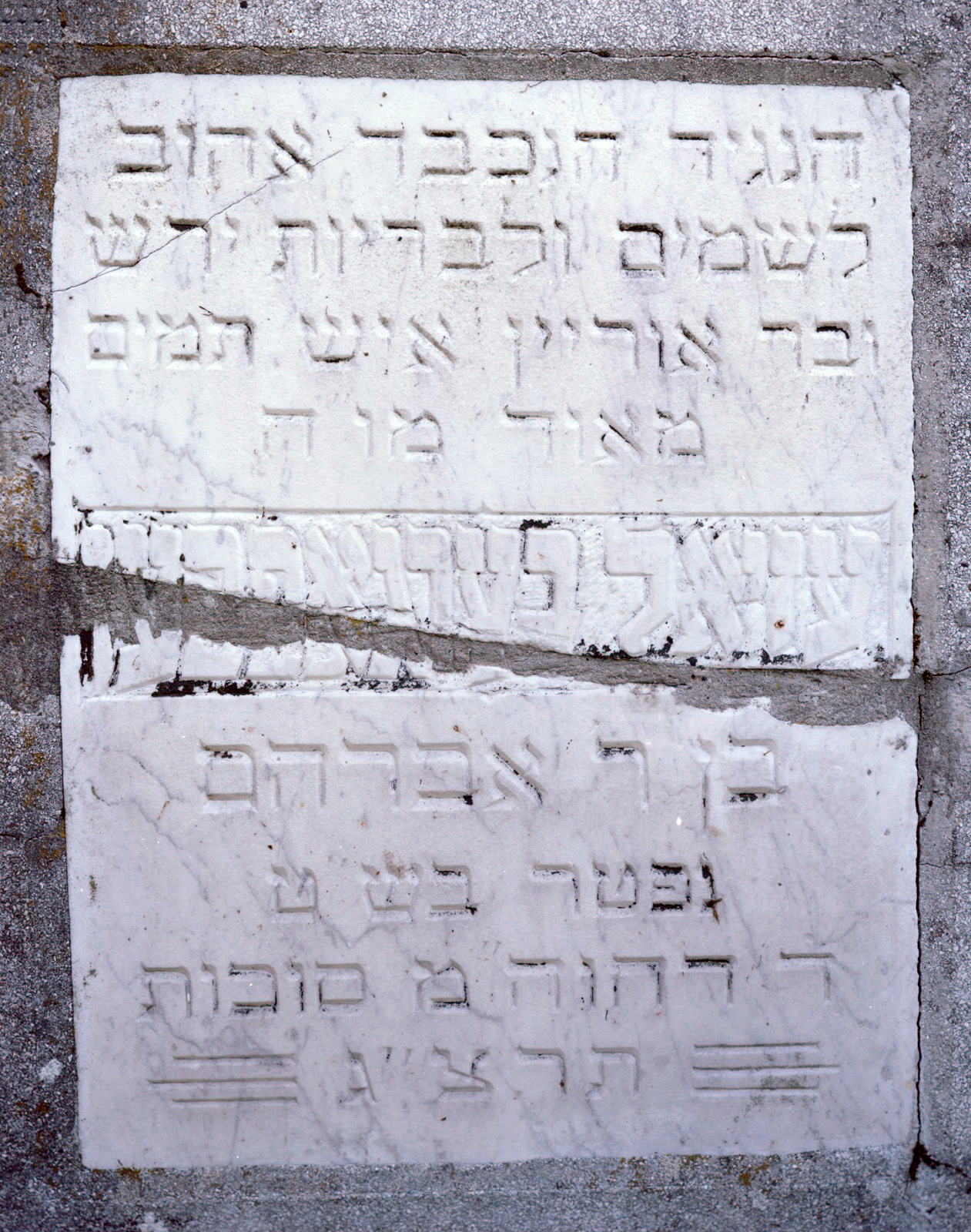

Grave of the sage Yom-Tov Lipman Heller, Kazimierz, Kraków

Class meeting in the Jewish Studies Department of Jagiellonian University, Kraków

Pilgrim to the grave of Moses Isserles, Kazimierz, Kraków

Polish folk art recreating Jewish life, Pilzno

Open-air exhibition on Jewish life in prewar Oświęcim, the city famous for the Auschwitz camps

Ruins of a beis medrash, Przemyśl

Holocaust memorial, Mielec

Restaurant owner with recovered Torah scroll, Proszowice

The Jewish cemetery, now a bus station, Przeworsk

Renovated synagogue in the village of Wieliki Oczy

The Bełżec death camp, where most of the Jews of Galicia were murdered

The Popper synagogue, Kazimierz, Kraków

Students tour the attic of the Gmina building, hiding place during the war, Kazimierz, Kraków

Plac Bohaterów Getta, center of Kraków's wartime ghetto

Former mikvah, Tarnów

Wedding at the Jewish Community Center, Kazimierz, Kraków

Ethnographic display with anti-semitic elements, Kraków

Wedding, Kazimierz, Kraków

Ruins of the Chevra Tehilim synagogue, Kazimierz, Kraków

The Polish and Jewish cemeteries of Lubaczów, side by side

Interior of a courtyard synagogue, now a glass workshop, Kazimierz, Kraków

Bachelor apartment, formerly the town mikvah, Zator

Bernard Offen, Holocaust survivor and activist, Płaszów camp

Onsite museum re-creation of the camp at Pustków

Ruined synagogue, Przemyśl

Museum re-creation of the Płaszów camp, Kraków

Interior of the synagogue at Dębica

Folk art synagogue, Pilzno

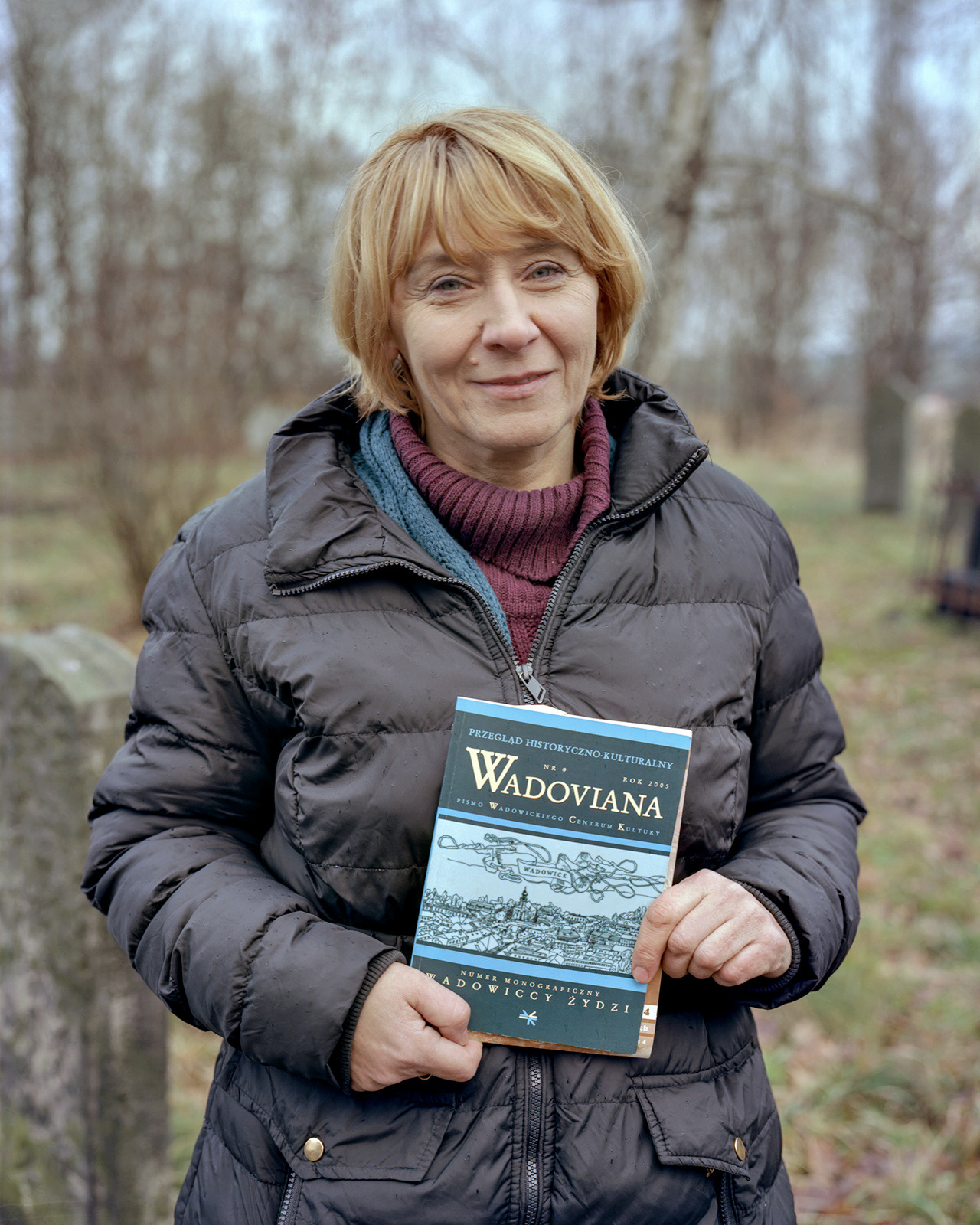

Mended tombstone, Wadowice

Museum exhibition on Jewish life in Oświęcim, Auschwitz Jewish Center

Reconstruction of a wooden synagogue, Sanok

Jewish and Christian mass graves, Zbylitowska Góra

The well cared for Jewish cemetery, Wadowice